Imagine the government decided to pass a law requiring all persons under eighteen years of age to wear a government-approved uniform at all times when in public. The justification for the law might be to give police an easy way to identify minors.

How would you respond to such a law? Would you see it as an unjustifiable attempt to limit your freedom or your individual identity? Would you accept it as a legitimate requirement for law enforcement and public security? If the people felt the law was wrong, what power would they have to change it?

These are important questions that relate to how Canada has built upon the concepts of freedom, democracy, and individualism laid out by the great liberal thinkers of the past. An understanding of how evolving views on liberalism affected the political power and individual rights in this country will be important as you tackle future challenges in this course and the challenges that will face you as a citizen of Canada.

In this lesson, you will explore the question: To what extent has Canada interpreted liberal principles and integrated them into its governmental structure?

The most fundamental component of democracy is the idea that the ultimate power to govern lies with the governed. In contrast to authoritarian systems, liberal democracies value the will of the people as a part of the decision-making process and provide a number of ways for people to express their will to the government. As you remember, in ancient Athens, that was only partially true. Only males who were verifiable citizens of Athens could take part.

inWhile Canada has had a democratically elected government since 1867, universal suffrage (the right to vote) was not achieved until much later. At the confederation, the requirements for individuals to vote in federal elections were set out by provincial governments, so they varied from province to province. Typically, however, the franchise (the right to vote) was restricted to males who owned property of a certain value. Women, Indigenous, and many ethnic minorities were prohibited from voting. In a sense, voting rights in Canada were not significantly more advanced than they had been in ancient Greece.

A democracy can be either direct, in which all the people vote on all government decisions, or representative, in which the people vote for representatives who then make decisions on issues.

As you have discovered, the understanding of who should have the right to vote and run for political office in Canada has broadened considerably over the history of the nation. Canadians can now rightly claim to have a much more inclusive democracy than existed in ancient Athens, but Canada still has some problems that plagued ancient Greek democracy, only they are much larger.

You should recall from previous lessons that ancient Athenians engaged in direct democracy, that is, each eligible voter had the right to vote on each issue before the government. In Athens, not everyone could show up all the time to vote. People were sometimes too busy to take the time to attend assemblies or to familiarize themselves with the issues under debate.

Flash forward to modern-day Canada with a population of over 35 million people. Direct democracy would be very difficult to implement here. It would be very difficult to provide a venue for millions of people to express their opinions, consider all the opinions of others, debate suggested policies, and then hold a vote on which one to follow. As well, Canada is a large and complex nation. There are multitudes of issues that need to be dealt with. Laws must be carefully written and detailed. A single bill (a proposed law under consideration by the government) can be pages and pages long and deal with subject matter that is unfamiliar to many individuals. Most people in Canada, like many ancient Athenians, could not, or would not, spend the time to review all proposed laws.

Direct democracy, then, is used only in rare instances in Canada. If elected politicians see an issue as so important that they wish the electorate (the citizens within a population who are eligible to vote) to play a key role in decision-making, they may opt to hold a referendum (a direct vote by the electorate on an issue of importance) or a plebiscite.

A referendum is typically a legally binding verdict of the people which must be acted upon by the government in the form of a law. Sometimes, referendums are declared non-binding.

A plebiscite is little more than an expression of public opinion; it is advisory only and not binding on the government, whether federal, provincial, or municipal.

Different countries use these terms differently or interchangeably. Sometimes, jurisdictions hold non-binding "referendums", such as in New Zealand (really a plebiscite). Even the UK "Brexit referendum" was non-binding. The leader of the government could have asked Parliament to decide, regardless of the referendum result.

Plebiscites and referenda are used more frequently at local levels of government. Citizens may be asked to vote on a local issue at the same time they choose their city councilors. National referendums are far rarer. There have been only three national referenda in Canada since the confederation. The most recent, held in 1992, asked Canadians if they wished to make changes to the country’s constitution. These changes were outlined in a document called the Charlottetown Accord which, among other things, proposed changes to the status of Indigenous and to Quebecois society within Canada. In the referendum, Canadians rejected the proposed amendments to the constitution.

Holding a referendum on the Charlottetown Accord was expensive. It was also divisive. Many Quebeckers saw the result as a rejection of Quebec’s distinctiveness within Canada. In 1995, Quebec held its own referendum on whether or not the province should remain in Canada, or become a sovereign nation. By the narrowest of margins, Quebeckers chose to remain part of Canada.

Since the problems associated with direct democracy make it generally unworkable in a large nation, Canada ensures that ultimate decision-making power rests with the people by using representative democracy. In Canada, elections are held in which votes chose individuals to represent them in government. Should the representative not be sufficiently attentive to the will of voters, they may be voted out of office in the next election. In fact, in British Columbia, in cases where many citizens feel a particular representative is not representing them adequately in the provincial legislature, voters may petition for a recall election. They may choose to replace their representative long before the next general election.

Understanding exactly how representative democracy works in Canada is important, not only because as a citizen you should understand how your government is chosen, but because some people suggest that there are imperfections in the Canadian system that undermines the true spirit of liberalism.

The 2-minute video below explains how representative democracy works in Canada:

At the national (federal) level, representatives are referred to as Members of Parliament (MPs). At the provincial level, there are varying titles applied to representatives, including Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), Members of the Provincial Parliament (MPPs), or Members of the National Assembly (MNAs).

While eligible voters vote for the individual candidates whom they believe will best represent them in government, the actual power to govern is determined by which political party wins the most seats in the House of Commons.

The video below explains how the number of seats won in an election determines who has the power to govern the country:

Once people are elected to power, how can citizens be assured that those elected will not abuse that power?

In Canada, the power of government is limited by the following factors:

The rights of individuals are also enshrined in the Constitution in a document called the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

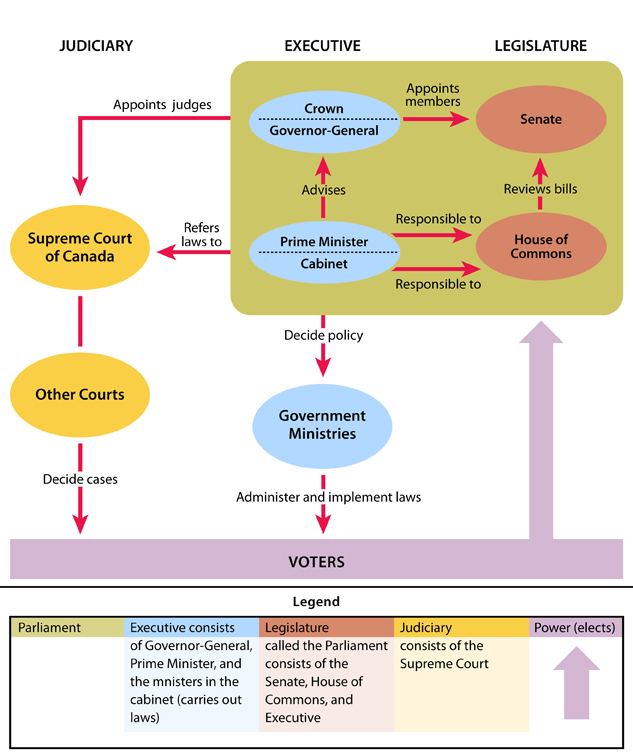

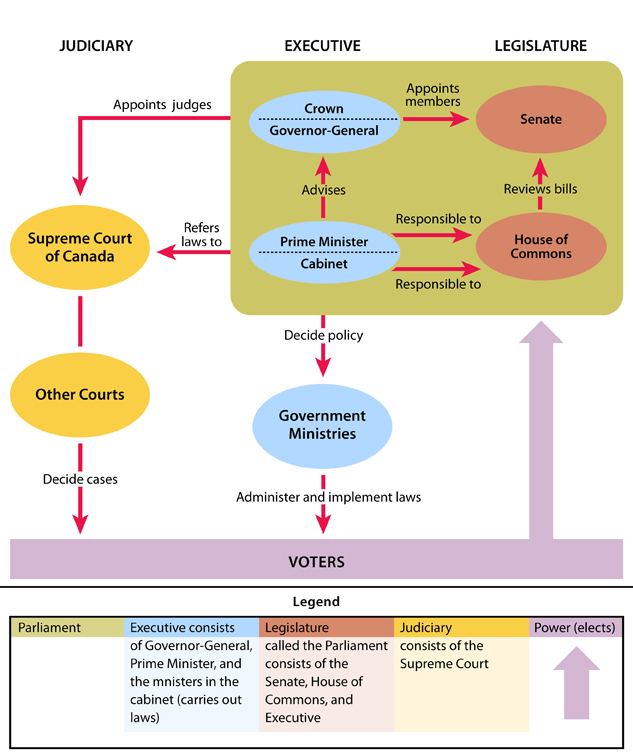

Following the principles set forth by Charles de Montesquieu and others, the various powers of government in Canada are divided up among three branches. The following “Branches of Government” piece explains the branches of government in Canada.

One of the main differences between democracy and liberal democracy is the recognition that the rule of the majority should not undermine the rights of minorities. In Canada, the power of the majority is limited in several ways.

The bicameral legislature you learned about earlier was put in place to help compensate for the fact that the majority of Canada’s population living in one region, might be able to use its political power to override the interests of minority populations living elsewhere in the country.

Representation in the House of Commons is achieved through representation by population. Therefore more heavily populated regions of the country have more representatives in the House of Commons and, consequently, more political power. Each riding has one MP. Which parts of the country have the most representation in the House of Commons?

Seats in the Senate are proportional representation, to some degree, on a regional basis. Examine the table below.

| Province/Territory | Number of Senate Seats |

|---|---|

| British Columbia | 6 |

| Alberta | 6 |

| Saskatchewan | 6 |

| Manitoba | 6 |

| Ontario | 24 |

| Quebec | 24 |

| New Brunswick | 10 |

| Prince Edward Island | 4 |

| Nova Scotia | 10 |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 6 |

| Yukon | 1 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 |

| Nunavut | 1 |

Under the present arrangement, the western provinces combined have roughly equal voting power in the Senate to either Quebec or Ontario. Some of the maritime provinces have 10 senate seats each, despite having relatively small populations compared to the Western provinces. This arrangement was concluded in 1867 at Confederation when the maritime provinces had a much higher population than the West.

Some Canadian organizations and governments use consensus decision-making rather than voting to decide on a resolution to an issue. This allows the opinions of all representatives to be heard.

Interest groups represent the will of specific groups of people by influencing elected officials to vote on issues based on the groups' values and beliefs. In cases when people feel that their will is not being followed by government representatives, they may express themselves through public protesting or rioting.

Watch the video below to understand where the Canadian government gets and spends its money. Do you think some or all of this should change?

Canada is a Constitutional Monarchy. King Charles III is our head of state. The Governor General is the King's representative in Canada. The King appoints the Governor General on the recommendation of the Prime Minister.

The Canadian Constitution limits the King's powers so he is considered a figurehead. The Governor General is also considered primarily a figurehead but the King still has what are called Reserve or Prerogative powers.

The King through the Governor General grants royal assent before a bill is passed into law in Canada. Technically, the Governor General has the power to delay or refuse royal descent. The King is responsible to ensure a functioning government. If the government acts unconstitutionally in an extreme case, the King technically has the power to dismiss the Prime Minister or the power to dissolve Parliament.

Bicameral legislature: a legislature that is comprised of two legislative "houses", both of which must approve a bill before it becomes law

Bill: a proposed law under consideration by the government

Coalition government: in a parliamentary system, the term used to describe a situation where two or more rival parties agree to work together, combining the seats they have won in an election in order to have sufficient total seats to form the government

Consensus decision-making: develop and decide on proposals with the aim, or requirement, of acceptance by all

Direct democracy: all people vote on all government decisions

Electorate: the citizens within a population who are eligible to vote

Franchise: the right to vote

Interest groups: represent the will of specific groups of people by influencing elected officials to vote on issues based on the groups' values and beliefs

Majority government: in a parliamentary system, the term used to describe a situation where the governing party has more than 50% of the available seats in the legislature

Minority government: in a parliamentary system, the term used to describe a situation where the governing party has more seats than any other party in the legislature, but has less than 50% of the total seats

Plebiscite: the direct vote of all the members of an electorate on an important public question such as a change in the constitution

Proportional representation: gains seats in proportion to the number of votes cast for them

Recall: a political process by which the electorate, by way of a new election outside of the time frame of regular general elections, may reverse a previous decision to elect an individual to public office

Referendum: a direct vote by the electorate on an issue of importance

Representative democracy: people vote for representatives who then make decisions on issues

Representation by population: a system under which individuals elected to government represent roughly similar numbers of citizens

Simple plurality system: an electoral system in which the winning candidate is the one who receives the highest number of votes; also called first-past-the-post

Single member constituency: a system under which a single individual represents the citizens of a riding or constituency

Suffrage: the right to vote in political elections

The Canadian government and Canadian society were founded on many of the basic principles of liberalism developed by Lock, Montesquieu, Mill, and others. Our government has been structured to provide representation to the citizens and give them the right to choose who will govern. Safeguards have been put in place to limit the power of those who govern once they are in power.

That said, the protection from the power of government and the right to participate in it has been selectively applied over the course of history in Canada. Many groups have been subject to majority tyranny, often targeted because of their race, ethnicity or religious beliefs. As Canada has evolved as a nation, our understanding of liberalism has changed as well. The list of rights associated with liberal democracy continues to be expanded and these rights are being applied more equitably in present Canadian society than in the past.

Despite these advances, many would argue that there is still room for improvement. Over the course of this lesson, perhaps you have identified some imperfections in the implementation of liberal democracy in Canada. If so, keep them in mind. In subsequent lessons, you will further explore many of these problems and make recommendations for solutions.

Research the evolution of the franchise in Canada. Create a voting rights timeline that shows when the following milestones were reached.

Check your timeline by identifying the approximate year in which each milestone on the road to universal suffrage in Canada was achieved. Make any required corrections to your “Voting Rights Timeline”. Check your work here

Do you know what your rights are under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms? You may be familiar with people being “read their rights” on TV crime dramas or most recently with people referring to their 'rights' when discussing the health measures of the last few years. What rights do Canadians have under the Constitution? If you don’t know, research and find out.

You may want to access the following additional resources.